Issues dealing with the growing pediatric airway are nothing new to dentistry. Bruxism, snoring, and even chronic allergies are conditions that deserve additional understanding if pediatric dentists are to be able to treat their patients the best way possible. In this article, four pediatric dentists ask Dr. T.J. O-Lee, chief of pediatric ENT at Loma Linda University, questions about the pediatric airway. His answers provide medical insight for pediatric dentists that help us construct a more complete picture of the complexities associated with the airways of our smallest patients.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

QUESTION:

“I’ve been asked, what percentage of children actually have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and need any treatment? What does science show about the actual impact of obstructed airways and how does this condition affect oral dental health? What about OSA in kids that have a lot of neck weight, diagnosis of ADD/ADHD, and huge tonsils? Do ENT specialists provide some general guidelines for answering the following questions: 1) what constitutes a treatable OSA condition in kids, 2) how do ENTs assess tonsils, and 3) when should tonsils be removed, or should they?” Paul Johnson, DDS—CALIFORNIA

ANSWER:

Childhood snoring puzzles many parents. They often complain, “Such a small body should not produce that kind of noise all through the night.” I have viewed enough parent-provided video clips to attest that the size of the child does not necessarily correlate with the volume or ferocity of their snoring. While snoring is annoying, it rarely requires medical treatment. It is, however, an indicator of a more serious condition—Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). OSA occurs in approximately 3–5 percent of the pediatric population. Its symptoms include snoring, mouth breathing, gasping / choking during sleep, daytime hyperactivity, behavioral / learning difficulty, and daytime fatigue.

While it is commonly expected that a fatigued child would be sleepy, such expectation is often unrealized due to fatigue-associated hyperactivity in young children. One useful diagnostic question I have come to depend on is this, “Does your child fall asleep in the car?” The car seat restrains the child and disables fatigue-induced hyperactivity long enough to allow the sleepy child to finally emerge.

If more objective evidence is needed, the gold standard for OSA diagnosis is the overnight sleep study, aka polysomnogram (PSG). This test measures many sleep related parameters and provides a series of numerical values to assess the presence / severity of OSA. These numbers are useful in many clinical situations, including the assessment of interventional efficacy. Although OSA can often be diagnosed by clinical symptoms, PSG can be helpful when parental observations lack certainty.

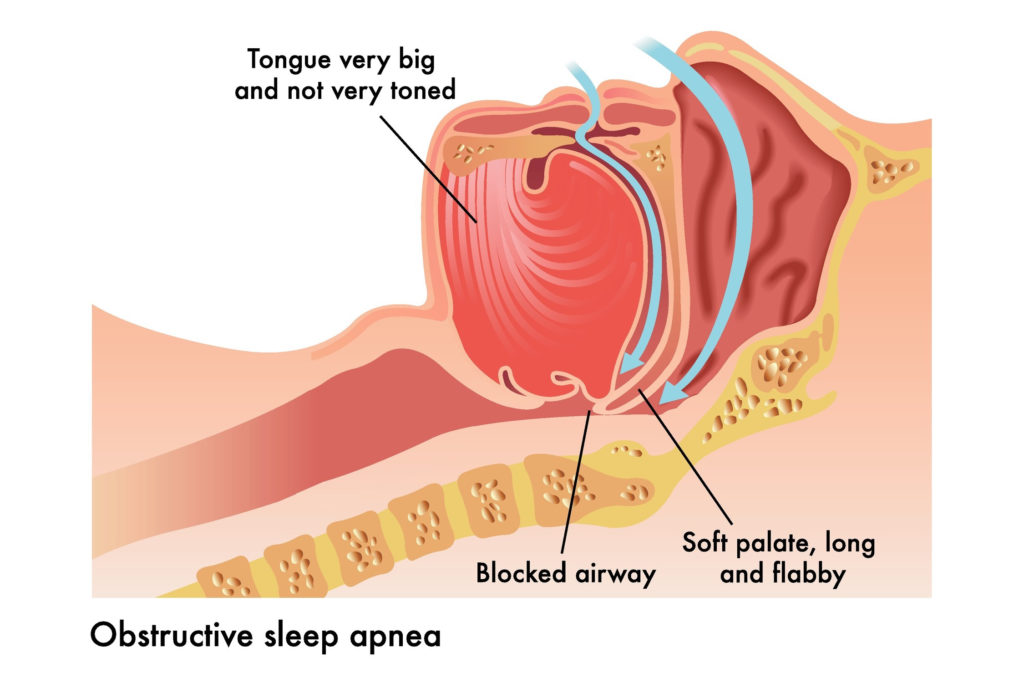

Adenotonsillar hypertrophy is by far the most common etiology for pediatric OSA. While it is tempting to classify the severity of OSA according to tonsil size, studies have shown that it is possible for impressive-sized tonsils not to be associated with OSA. Also, children with relatively small tonsils may suffer from OSA due to adenoid hypertrophy. While large tonsils do more frequently lead to OSA, clinical symptoms are much better predictors of OSA than tonsil size alone. Therefore, it is prudent to follow up any observation of large tonsils by asking parents a few questions regarding their child’s symptoms. “Does your child snore?” “Is she hyperactive throughout the day?” “Does he fall asleep when you drive around town?” These questions may prove helpful in uncovering potential cases of OSA.

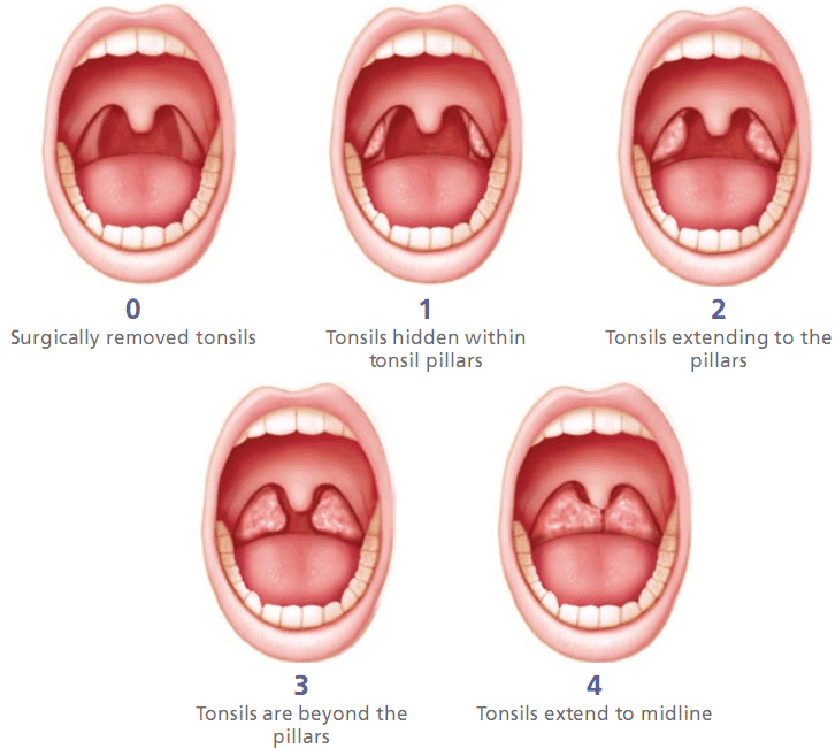

In the ENT world, tonsils are assigned a grade from 1 to 4. Each number approximates 25 percent of the available oropharyngeal space. If tonsils occupy approximately 60 percent of the available space, then they are grade 3. An alternative way to grade tonsils takes into account the relationship of the tonsils to the surrounding structures. If tonsils reside completely inside the tonsillar fossa, then they are grade 1. Grade 2 tonsils extend beyond the tonsillar fossa but do not touch the uvula. Grade 3 tonsils touch the uvula. Grade 4 tonsils touch each other.

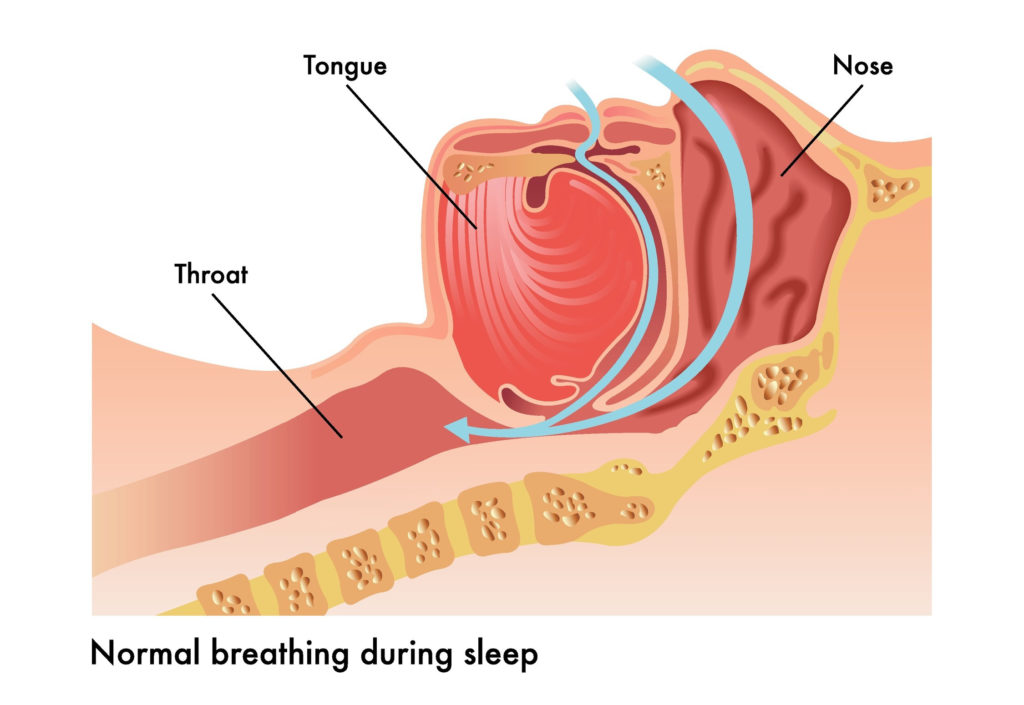

Mouth breathing is a common symptom for kids with OSA. Enlarged adenoids can obstruct the nasal passage necessitating opening the mouth to increase air flow. Prolonged mouth breathing throughout the night can dry the oral cavity and decrease saliva lubrication. This has been theorized to increase the rate of dental caries and cause adverse effects for oral health.

Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy surgery (T&A) is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the world. Approximately 500,000 cases are performed in the United States annually. It is the first line of therapy for pediatric OSA. The surgical success rate for T&A against pediatric OSA is around 80 percent. While CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) is often recommended for OSA treatment in adults, the higher success rate of T&A in pediatric patients makes surgery more desirable than CPAP. CPAP is often poorly tolerated in the pediatric population and has been known to affect mid-face protrusion over time.

For patients with clinical signs of OSA and enlarged tonsils, PSG may be optional. When the clinical picture is unclear, results of PSG may be helpful in guiding treatment decisions. Since even mild cases of OSA can be disruptive to a child’s learning and quality of life, treatment should be considered as early as possible.

Treating an Inadequate Airway

QUESTION:

“Biological dentists have been discussing among themselves whether it is possible to “grow” an inadequate airway. Have you heard of this, and is this possible? Also, some dentists have suggested that early orthodontic expansion may help with resolving airway issues. Is that true?” Joelle Speed, DDS—CALIFORNIA

ANSWER:

Time has always been a friend to airway surgeons. Many conditions, such as laryngomalacia, nasal stenosis, or tracheal stenosis, can improve as the size of the airway increases with growth. One of the last-resort interventions for a neonatal airway problem is to perform a tracheostomy. The principal behind the tracheostomy is to provide an alternate airway to allow additional time for growth. For many children, tracheostomy can be removed within the first two years of life.

Growth affects all aspects of the airway, but is most pronounced at its narrowest points, such as the nasal passage and the larynx. The equation for laminar flow resistance (Q) in a tube is equal to R 4 / 8 L (R=radius of the tube, =viscosity of the fluid, and L= length of the tube). As you can see, the flow resistance in a tube is inversely affected by the radius of the tube to the fourth power. This means even a small increase in the size of the airway can lead to a significant drop in airway resistance. The size of the child increases by several fold in the first two years of life; therefore, improvements in airway patency are often observed as well. The most critical period of anatomical airway resistance is within the first couple years of life.

I personally do not have much experience in orthodontic expansion treatment of airways, but such expansion would likely have to be instituted early to make any significant impact.

Bruxism and Problems with Grinding

QUESTION 1:

“Parents ask me all the time about grinding in preschool and elementary age children. Typically, I do not recommend anything other than warm compresses and TMJ massage by the parent as part of a child’s bedtime routine. An exception is when cases of grinding are associated with GERD. In those cases, we sometimes have to get invasive and go with full-coverage options such as using zirconia or stainless steel crowns to stop extreme sensitivity and allow the kids to eat. I’m typically not in favor of any “night/ bite-guard” type of appliance in growing kids, but I want to make sure we’re not missing something.” Mandy Ashley, DMD—KENTUCKY

QUESTION 2:

“The number one question we get in our office from parents is about grinding. I personally believe that it is 100 percent related to airway and allergies. I’d love to know if that is what ENT specialists believe. And since we can’t really treat grinding in little kids, what do they think about treating the airway first? What about things like using nasal spray before bed all the way to the extreme of performing a T&A—removing tonsils and adenoids?” Andi Igowsky, DDS—WISCONSIN

ANSWER:

Nighttime teeth grinding or sleep bruxism occurs in up to 30 percent of children. There is an age-related prevalence distribution that seems to peak around age 6. Prevalence tends to decline when children are around 9- to 10-yearsold. While the exact cause of the condition is unclear, some degree of bruxism may be considered physiologic and promotes normal growth of the facial skeleton. For this reason, sleep bruxism itself does not require intervention.

Problems with bruxism arise when children start to experience adverse effects such as pain, excessive dental wear, or sleep disturbances. Some authors advocate treatment for bruxism in children over the age of 10, when physiologic bruxism starts to decrease.

A meta-analysis of childhood bruxism treatment in December 2019 by Chisini, et al, summarized the effectiveness of many forms of treatment. The use of nighttime occlusal splints decreases parent-reported bruxism by 77 percent and improves conditions such as headache and muscle discomfort. Physical therapy also provided similar benefits. Pharmacologic agents such as Flurazepam, Trazadone, and Hydroxyzine have been shown to reduce bruxism and morning pain. Palatal expansion using rapid maxillary expansion devices for six to eight months reduced bruxism in 58 percent of children.

Some people hypothesize that sleep bruxism can be triggered by OSA. It is postulated that the unconscious effort to keep one’s airway patent can lead to an increase in autonomic drive. This contributes to the stimulation of upper air way muscles. This increased drive can then be a trigger for muscles of mastication and cause bruxism.

While sleep bruxism is not considered to be a condition requiring airway surgery, any improvement in bruxism from treatment of OSA is certainly welcomed. It is, therefore, reasonable to inquire about symptoms of OSA when questions arise about bruxism. Asking airway screening questions in the pediatric dental office is likely to be very helpful in the diagnosis and treatment of OSA. Simple questions about snoring, nighttime awakening, hyperactive behavior, or daytime somnolence can increase parental awareness about OSA. Symptomatic children should be referred to their primary care provider for further evaluations (such as PSG) or treatment (possible ENT referral). More conservative measures to improve airway patency such as allergy treatment and nasal steroids should also be considered in patients suffering from chronic sneezing, nasal drainage, or watery eyes.

Conclusion

Care of the pediatric airway and oral health are intimately related. Pediatric dentists are well positioned to screen for OSA and other airway problems due to the frequent opportunity they have of observing their patients’ oral anatomy. Many of the signs and symptoms for OSA are subtle, and parents may tend to overlook them. But a vigilant pediatric dentist who observes signs like tonsil hypertrophy and mouth breathing may assist ENT colleagues in the identification of airway problems. Asking screening questions about snoring, nighttime awakening, daytime hyperactivity, and sleepiness during car trips can elicit further clues about a child’s nighttime sleep quality. By working together, pediatric dentists and pediatric otolaryngologists can significantly improve the breathing quality of our youngest patients.